- UK’s FCA Guidance on Structured Products

- USA’s SEC Bulletin on Structured Notes

- Investopedia: Why Structured Notes Might Not Be Right for You

- Forbes: Structured Note Buyers Be Warned

- Investment News: Structured notes offer too-good-to-be true returns

- Wall Street Journal: Risks of Insuring Against Risks

- Straits Times: Retail Investors, Steer Clear of Complex Structured Notes

- Forbes: Why You Should Avoid Zombie Structured Notes

- Alpha Architect: Structured Notes: The Exploitation of Retail Investors

- CBS News: Investors Lose $113 Billion on Complex Investments

- MoneyWeek: Four Reasons To Avoid Structured Products

- GillenMarkets: Why Structured Products Are Such A Poor Purchase

- Mahany Law: A Bad Idea Resurfaces

- Forbes: Buffered Return Enhanced Notes: Bad Investment Choice That Sounds Good

19/10/2019. If you are an ordinary retail investor, then financial Structured Products are probably not right for you.

Here’s why:

1. They

are too complex for most ordinary investors to understand.

2. They

are expensive in both manufacture and distribution, but those costs are hidden.

3. They can be promoted by financial salespeople who themselves can’t explain how

they work.

4. They

introduce additional layers of risk on top of the normal market risk that

investors expect.

5. They

do not adequately compensate investors for the additional costs or risks.

In the current economic climate, some ordinary investors

might feel nervous about market volatility.

As the UK’s FCA

(formerly FSA) previously stated: “This leads consumers to be attracted

by products that claim to offer a degree of security and also promise higher

returns. Firms have responded by

manufacturing and marketing products that aim to deliver higher returns.”

Rich pickings for financial salespeople! But be aware: “In many cases, both the

benefits and the risks of these products are opaque.”

Don’t get me wrong - structured products can be a useful tool in the kit-bag of a wealthy and sophisticated investor. But if you’re an ordinary retail investor, the purpose of this article is to help you decide if a structured product is right for you.

Rule 1: Don’t let Complexity Distract You from the Obvious

First, here is a brainteaser:

“In a football knock-out tournament, the first round has 32

teams, and in each match a team is knocked out.

The winning 16 teams then enter the next round, again with each match

knocking out a team. And so on. Rounds continue, until at the end there remains

one winning team. Question: how

many matches have been played in total?”

The answer is approached by stating the obvious. Only one team has won, so 31 teams have been

knocked out. Therefore, exactly 31

matches must have been played.

Here’s another statement of the obvious: the financial industry

creates and sells structured notes to make money. From you.

Common sense says Don’t invest in what you don’t

understand. If your financial

advisor suggests you buy a structured note:

1. First,

ask him or her to explain how it works, in detail, and what the risks are;

2. Next,

ask what other options you should consider instead (Important! There are

always options..);

3. Finally,

ask what commission they will be paid if you buy the structured note.

If you’re uncomfortable with the response, then walk

away. It’s that simple.

What Is A Structured Note?

Structured notes are synthetic investments, engineered by

the financial institution through a combination of financial instruments such

as options, equities and equity indices, and debt securities. A structured note is a fixed term

investment, and common terms are in the region of 4 to 6 years.

Typically, a structured note will offer a degree of capital

protection, plus a return to the investor if specific conditions are met. The

resulting returns can simulate that of an actual investment, but according to a

formula that depends on how the product has been engineered. For example, capital protection may be broken

if certain downside ‘barriers’ are breached, and gains may be capped or limited

if the underlying investments perform well.

General Classes Of Structured Note

There is a wide variety of types of structured note – you’ll

see names such as high income note, reverse convertible note, principal

protected certificates, booster certificates, enhanced yield notes, and

autocallable notes, amongst others. In

general, though, they can be categorised broadly by investment objective:

capital protection, income generation, and yield enhancement.

Example - Construction Of A Simple Structured Note

Suppose I want to participate in the upside of an index such

as the S&P500, but I want to protect my capital on the downside.

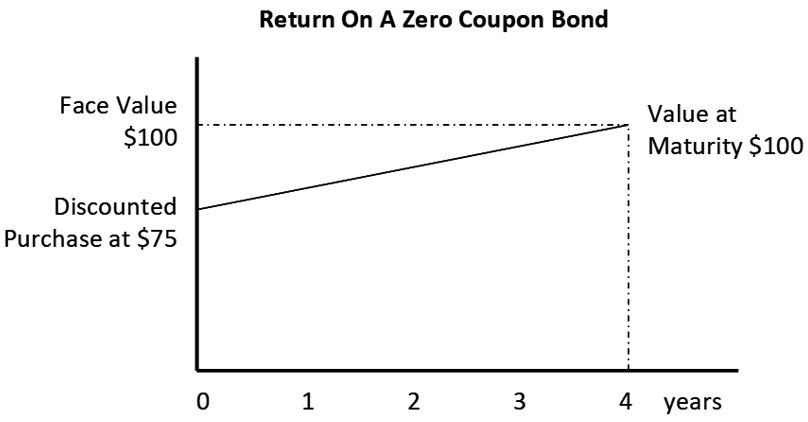

Firstly, capital protection can be achieved by buying a

‘zero coupon bond’, which is a kind of bond that pays no coupon (interest), but

is bought initially at a deep discount to the face value. Whilst the holder receives no income from the

bond, he does receive the face value at the maturity date.

Here’s an example for a four-year zero coupon bond:

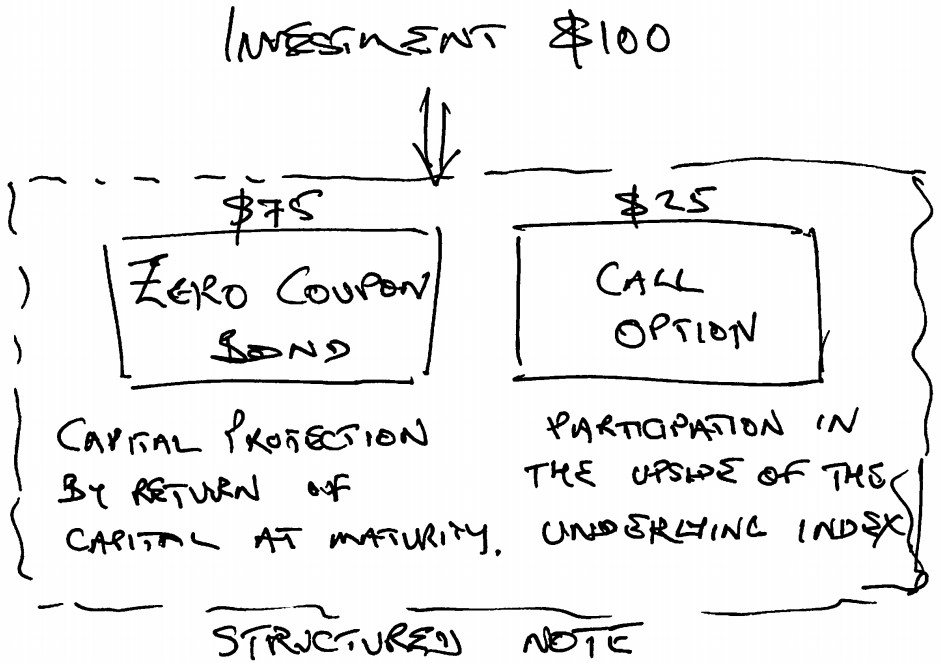

That leaves $25 to address the upside. I can use derivatives, such as options, to

achieve leverage on the target investment (in this case the S&P500 index). Suppose I could find a call option that gives me

4 times leverage on the index. Thus, a $25

option would give a return equivalent to $100 invested in the S&P500 in a

rising market, whilst in a falling market the option could expire

worthless.

Hey presto, I’ve created my theoretical structured

note. 100% protection if held to term,

plus full participation in growth of the S&P500 index. Even if the index has fallen, I’ll still get

back my initial investment.

Figure: Example of a simple Structured Note

What I have created is a ‘principal protected’ structured note. By using different types of derivatives

instead of simple options, and different debt securities or other methods for

insuring capital, we have flexibility for creating an endless variety of synthetic

investments.

So far, so good, right?

So, now time to look at the problems.

Structured Notes are Complex, and often have Limits on Protection, Performance or Both

The example I described above is just the bare bones, the

chassis, of a structured note. In

general, they’re substantially more complicated.

Fully capital protected structured notes are very expensive

to provide, especially when interest rates are so low like they have been for a

while. The price of a zero coupon bond =

M/(1+i)^n where M is maturity value (face value), i is interest yield divide by

2, and n is years to maturity times 2.

For example, if the interest rate is 2%, a $100 four-year

zero coupon bond will cost about $92.35.

In other words, the cost of capital protection severely restricts funds

available for the purchase of derivatives for upside participation.

Ways of keeping costs down...Ahem.. making the note more ‘attractive’ to investors, include:

Soft protection – meaning there’s a limit or

‘barrier’ on the downside protection, such that if the underlying index stays

above the barrier (eg. 70% of the level on the issue date), then capital

protection is maintained in full; but if the index falls below the barrier,

then protection is lost and capital is returned as though it had been invested

directly in the underlying index.

This is an issue because: one of the major

justifications for buying a structured note is capital protection; breaching your

protection barrier in the event of a market crash could be a seriously bad

scenario.

Capped maximum returns – meaning you may not receive

full returns of an index if it performs better than a certain figure. For example, the performance may be capped at

20%, in which case if the underlying index such as S&P500 grew by 30%,

you’d still only get 20% returns.

This is an issue because: you are locking your money

away for many years; to not participate fully in the growth of markets could

cost you dearly.

Structured notes can have huge variety of ‘features’ to make

them seemingly ‘better’ to investors; the above are just two of the common ones

to be aware of.

Cost Of Structured Notes

Structured products involve a lot of complicated financial

mathematics, and the involvement of several departments and staff within the

bank or institution that issues them.

And of course, they have to make financial sense not just to the issuer,

but also the distribution channel. The guy

or gal who sells them to you wants their piece of the pie too. These are extra layers of cost over the top

of the underlying instruments. Are you

getting good value for that extra cost?

Liquidity Risk and Opportunity Cost of Structured Notes

You might have been told that there is a secondary market

for your structured note, but beware: demand is generally thin or non-existent. Resale prices can be very low,

naturally. The issuing bank would rather

be selling new product, than recycling old.

Unless faced with a terrible emergency, you should consider your cash as

locked away in the structured note until maturity, i.e. many years.

This is where we uncover an undiscussed but significant cost of structured products – the ‘opportunity cost’ of locking your money away for years. Perversely, the very reason why many people buy structured notes is exactly the reason why they should not.

By definition, if you are thinking of buying a structured

noted, then you have at least a medium-term horizon, and probably a lot

longer. But the thing is, you’ve worked

hard for your money, and you are feeling nervous about ‘the markets’. So, you kind of like the idea of a capital

guarantee.

Alright then, go for it.

A year passes; what happens if there actually is a market

crash? You’re feeling all smug about

your capital protection, right? Well,

maybe. But consider what we all know - the

best time to buy equities is when there’s been a downturn. For example, post the 2008/09 global

financial crisis, the S&P500 delivered a total return of 85% in three

years from March 2009.

If you have at least a medium term horizon, and think there might

be a market downturn, then the last thing you should be doing is locking

away your money for years – because you could end up missing out on the best

buying opportunity in decades.

A properly diversified global portfolio, with an asset

allocation that matches your investor risk profile, is almost always a better long

run solution for an ordinary investor.

Another Form Of Opportunity Cost – You Are Not Actually Participating in the Underlying Index!!

Structured notes include financial smoke and mirrors that many

ordinary investors will never realise.

Your financial salesperson may say to you – “The underlying investment

is the S&P500 index, so you’ll get the returns equivalent to that”. No, you won’t.

An index such as the S&P500 reflects the daily price changes

of the constituents – in this case the largest 500 companies listed in the USA. But those companies pay dividends, and the price

movement alone does not represent the total returns to an investor in those

companies.

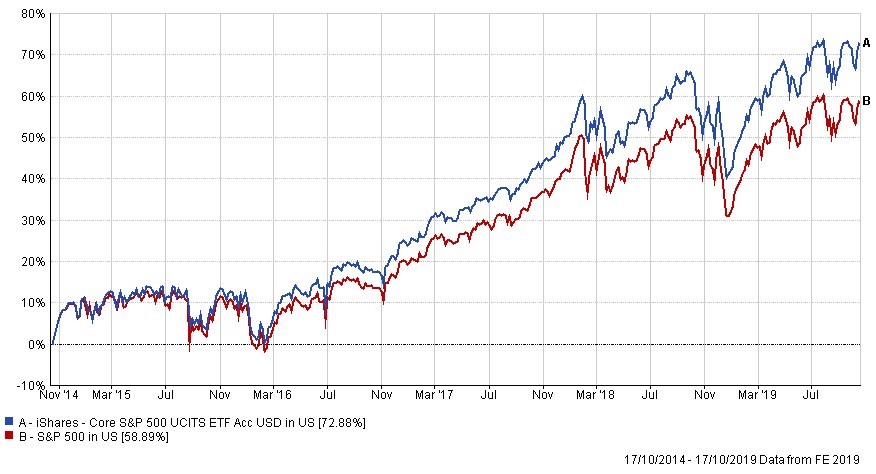

See at the chart below.

In the last five years, the S&P500 index has risen 59%. Pretty good.

If you hold a structured note that is linked to this index, you might feel

pleased.

But what if instead of holding the note, you had simply

bought an ETF that tracks the same index?

You would have been entitled to the dividends as well. With dividends reinvested, over the same

period, the total return to an investor in the iShares Core S&P500 UCITS

ETF would have been 73%.

59%, instead of 73%.

That’s a pretty big sacrifice for the privilege of capital protection,

that you probably don’t need anyway.

Counterparty Risk Of Structured Products

Return of capital depends on the credit-worthiness of the

bond issuer in your structured note. The

bond issuer may not be the issuer of the structured note itself – it could be a

bank or other financial institution.

So let's be clear: When it comes to structured products, "Protected" does NOT mean "Guaranteed". Your capital is at risk if for some reason the issuer cannot repay the debt. This is called counterparty risk, and when looking at structured products it is important to know which institution is holding your capital, and what its credit rating is.

Also be aware, since zero coupon bonds are expensive in times of low interest rates, your structured product issuer may be tempted to get them cheaper by buying them from banks with poorer credit ratings.

So let's be clear: When it comes to structured products, "Protected" does NOT mean "Guaranteed". Your capital is at risk if for some reason the issuer cannot repay the debt. This is called counterparty risk, and when looking at structured products it is important to know which institution is holding your capital, and what its credit rating is.

Also be aware, since zero coupon bonds are expensive in times of low interest rates, your structured product issuer may be tempted to get them cheaper by buying them from banks with poorer credit ratings.

What Are The Alternatives?

The financial industry has a terrible reputation in UAE, principally

because of historically poor regulation here.

This has created a landscape where a lot of financial marketing is deliberately

negative, designed to play on the fears of the investing public. “Don’t invest in that fund, it’s bad,” or “don’t

buy that product, it’s expensive.”

The problem is that if alternative options are not

identified, then ordinary investors may be discouraged from doing anything at

all.

I believe it's cynical and wrong to sell complex and expensive products to retail investors, to exploit their fear of market volatility. Moreover, when I see investors holding structured notes in their long-term savings or pension pots, I cringe.

So, it’s my responsibility to outline better ways of investing your money

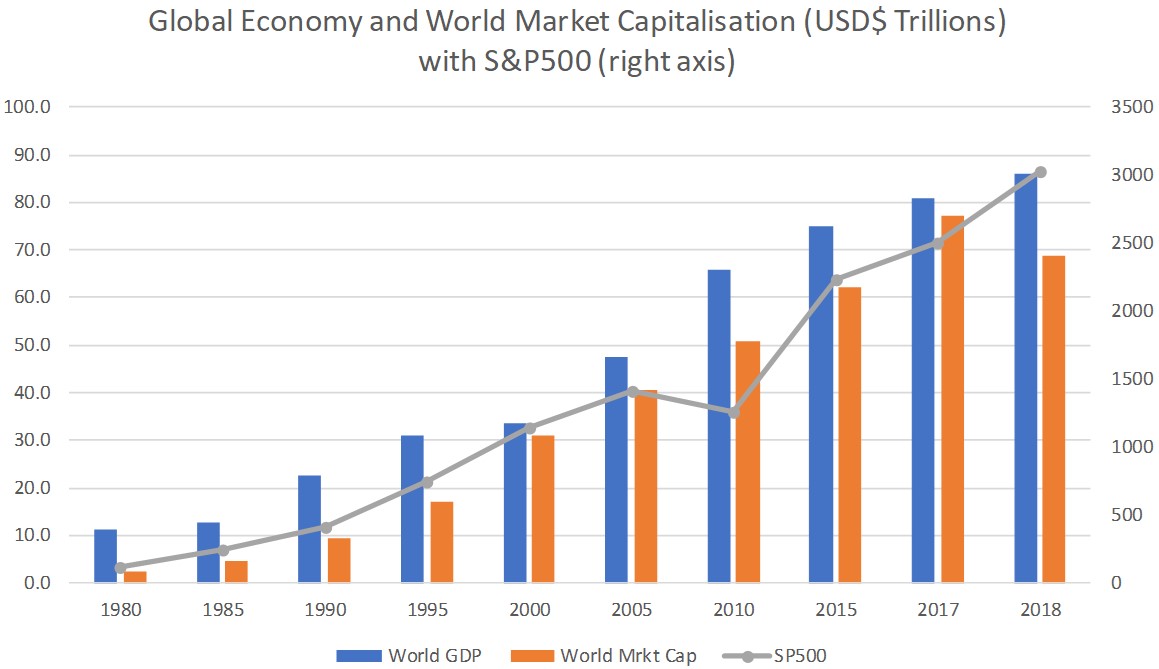

Firstly, let’s remind ourselves that in the long run, everything

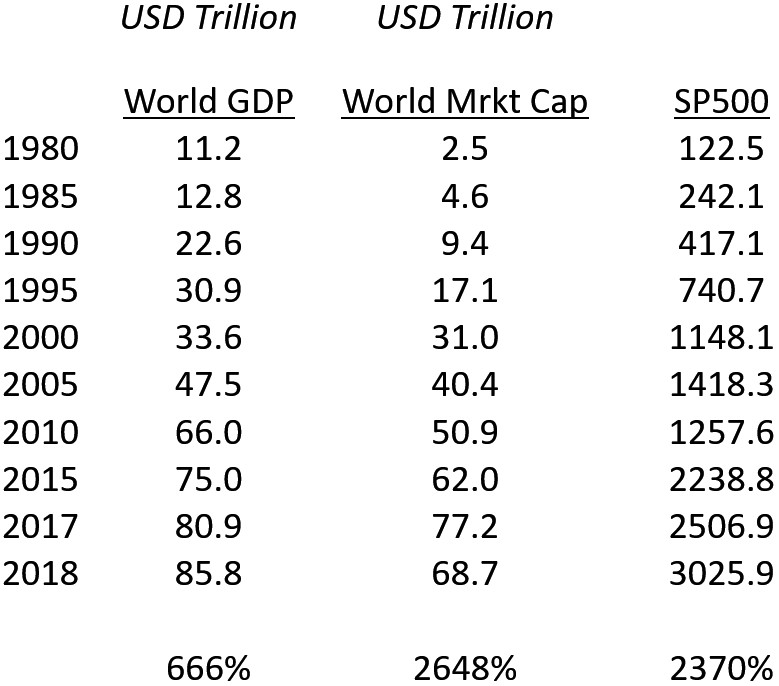

is going to be okay. See the chart below:

Global economic growth is relentless. Since 1980, global GDP has grown by 666%, and

world market capitalisation (value of listed companies worldwide) has grown by

2648%.

As investors, we participate in the long-term growth of the

global economy. Populations grow. Technology advances. Productivity increases. Societies shift from less-developed to advanced. Demographics shift from poor to middle-class. Yes, economies are cyclical, but we aren’t

going back to Roman times!

So, do we really need an expensive and restrictive capital

guarantee? Nope. All we need is a straightforward investment strategy

that reflects our time horizon and our investor risk profile.

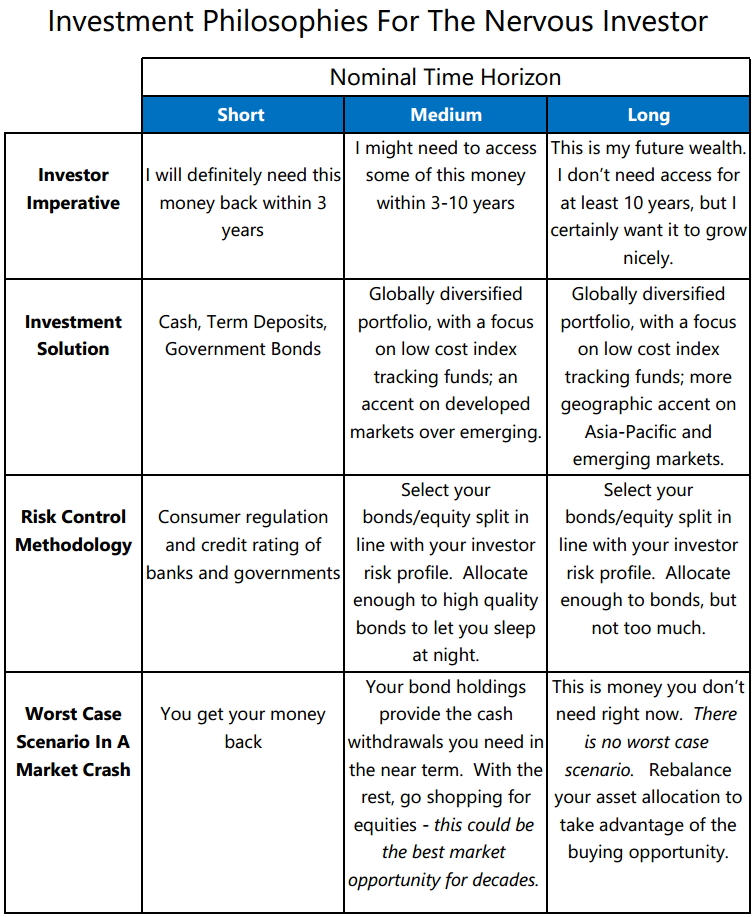

Every investor's situation is different, but the table below lays out a

framework that might be helpful to refer to, when discussing options with your

financial advisor.

Table: Investment Philosophies for the Nervous Investor

(c) 2019 Roy Walker. All Rights Reserved.

Please note opinions expressed in this article are my own

and not necessarily those of any other person or organisation.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Roy says: "Thanks for taking the time to leave a message, comment, or continue the conversation!"